Segment III – Ditching the Wig: Completing Treatment & Coping with Late Effects

by Rachel Trachten

1. Peach Fuzz

My love-hate relationship with the wig is mostly the latter. I hate being bald, I hate having cancer, and I hate needing a wig to look even remotely like my former self.

But the wig does serve its purpose. It’s top of the line, handmade with natural hair. It makes me look more-or-less like a regular person, albeit a fragile, skinny one. But the wig is heavy and makes my head itch and sweat. I constantly worry that it will get pulled off or slip sideways, revealing my weird alien-like head. In a recurring nightmare, a gust of wind carries all that hair off my head and into the ocean.

When a friend suggests trimming the wig, I take her up on the offer. She cuts off a good four inches, and I feel a rare bit of freedom. I take a certain pleasure in watching all that hair fall to the floor as she snips.

It’s January 1980 and almost time for my very last treatment. The final insult is one more dose of Cytoxan, the nastiest drug of all. It’s so toxic that I’ll spend the whole day at the hospital getting IV fluids to wash the poisons out. At home, one of my parents will awaken me every hour and convince me to drink eight ounces of water to prevent bladder or kidney damage.

By this time, Zach and I are living in a basement rental on Bank Street in the West Village. He’s taking some time away from Amherst for an internship in City Council President Carol Bellamy’s office. I’m back at NYU while finishing the chemo. We’ve been living together for several months, and he’s encouraging me to come back to our apartment after getting the Cytoxan. “I want to take care of you,” he says. “I’ll wake you every hour all night long.” But I’m not ready for him to see me throwing up. Over his protests, I go home to Brooklyn with my parents.

After that last dose of Cytoxan I’m officially finished with treatment. I experiment with thinking of myself as someone who no longer has cancer, but I’m still bald. I try head scarves and turbans but can’t come up with a better option than the wig.

Gradually, the cold winter days give way to spring. Grass and flowers pop up on the Manhattan streets, and my head sprouts a thin layer of peach fuzz. Zach says it looks adorable.

In our West Village neighborhood, it’s pretty much the norm to look different. Hair might be dyed pink or blue or gelled into spikes. Black leather and tie-dye are both in fashion, and torn fishnet tights are all the rage, especially with Doc Martens.

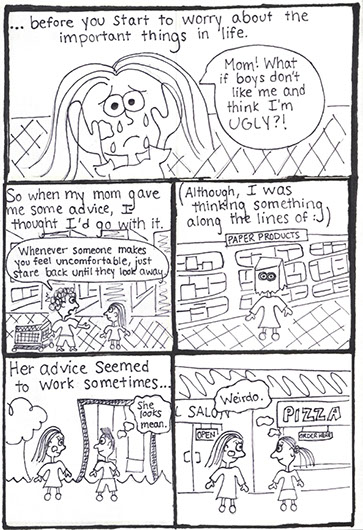

It’s a May afternoon, and I’m getting ready to leave our apartment for a class at NYU. The weather is unusually warm, and I can already feel sweat gathering where the wig presses against my neck. Just as I’m about to head out, I yank it off my head and toss it onto the sofa. I quickly lock the door behind me, trying not to think about what I’ve just done. With hair that looks more or less like a crew cut, I hit the streets. I’m awkward and self-conscious but love feeling the gentle breeze on my head. I study the faces of people I pass to see if they’re staring. No one looks twice as I stroll over to the campus.

In my art history class, an acquaintance greets me, and I sit down next to her. “Nice look,” she says. “Who cuts your hair?”

2. The Party

To celebrate the end of treatment, my mom wants to throw a party, but my dad resists. He admits that it scares him, that it feels like hubris: don’t flaunt your good fortune or it will be taken away.

But in the end, he changes his mind. As an unstated compromise, we decide to call the celebration a “Good Health” party as opposed to something that would bring the heavens down on me, like “Goodbye Cancer,” or “Hurray, I’m Cured!” One way or another, the party planning begins. My longtime friend Jeffrey, who goes on to become a successful chef, offers to do the catering.

I was 18 when I started treatment; I’m 20 when it ends. Soon I’ll be headed back to Amherst once again. Normal life will resume, won’t it?

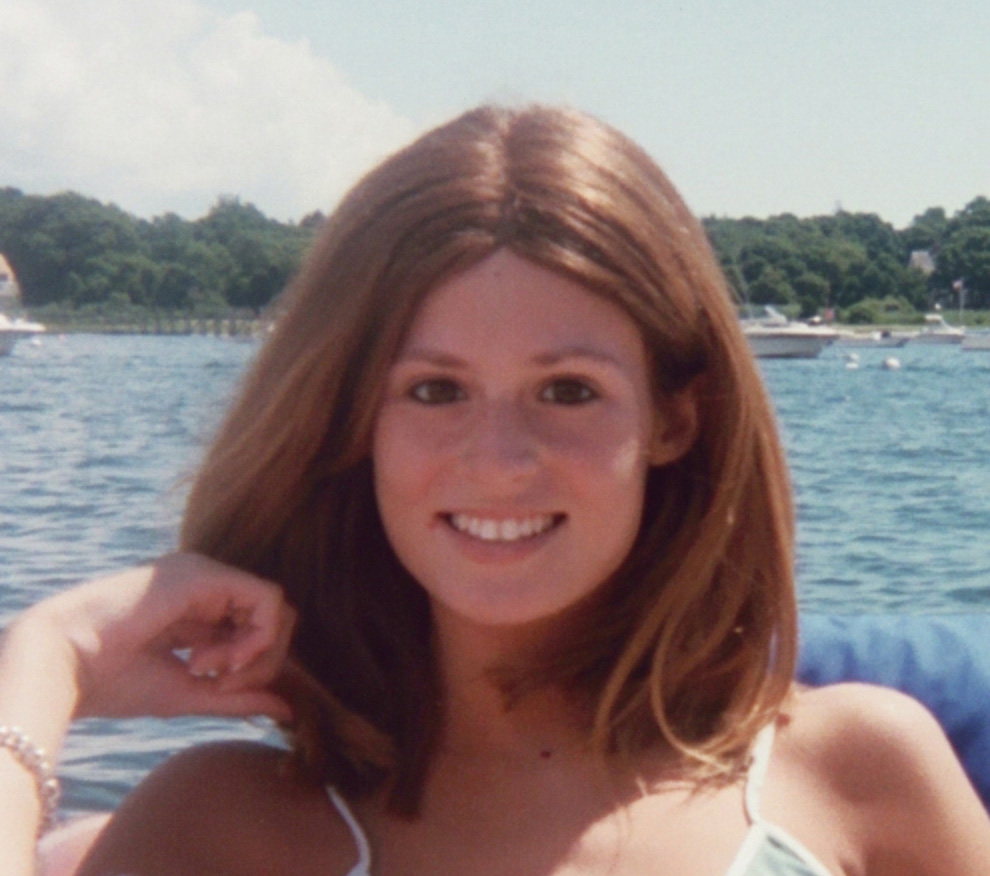

The party is in our Brooklyn backyard on a warm summer evening. Several months have passed since my final treatment, and my hair now approximates the Twiggy look. I’ve also managed to gain a few pounds, so I’m no longer a literal 98-pound weakling. I feel festive in a light-blue Marimekko sundress with tiny pink and green swirls.

That night, we celebrate my good fortune, my survival. People from all corners of my life show up with good wishes, gifts, and champagne. I watch Zach as he chats easily with my relatives and childhood friends. No gods strike me down as I mingle with guests and munch hors d’oeuvres. A chance of rain is in the forecast, but not a drop falls.

Still Breathing: Forty years later …

Sometimes people ask about the “gifts” of cancer or what I might have gained from the experience. I bristle at the question, though I can’t deny that illness has made me a more empathic person. And now that I’m well into middle age and my friends have their own medical problems, I’m often able to commiserate in a deep way. Unlike the experience of being surrounded by immortal teens, having peers in their 50s, 60s, and older means that many of us are grappling with health issues. Being healthy is no longer an absolute goal—it’s more a question of figuring out how to cope with whatever disease or disability comes our way. Although I do bring some wisdom to this struggle, the words “cancer” and “gift” don’t belong together in my world. It’s a gift I would have been thrilled to return.

That said, I’ve enjoyed many gifts over the years. Zach and I graduated from Amherst and were married two years later. We both wanted children, but my doctors advised against trying to conceive. Undaunted, we adopted a daughter and then a son. We moved across the country to California in 1998, when Julia and Alex were 10 and 5. I joined a local tennis team and imagined playing year-round for decades to come. Maybe the kids would even take up tennis and we could play family doubles.

Around the time of my final treatment, Doctor Murphy and other experts warned me that some patients start to experience cardiac problems and other “late effects” about 15 years after chemo and radiation. I vaguely took in this doom and gloom, but it all seemed so far away. At the time I thought, “maybe none of that will happen to me.”

But two years after the move, I started to feel the cardiac symptoms doctors had predicted. I found myself quickly out of breath while taking a jog or running for a forehand. My athletic singles game became a gentle doubles game instead.

By the time Alex was a young teen, I’d put my racket away for good. I recall a day we were walking up a steep San Francisco hill together. I had to stop and rest about every five steps. Alex was way ahead but circled back every now and then. “Aah, you’re so slow,” he teased. Then, “Will your heart ever get better?”

It was the first time he’d asked such a direct question about my health. I wavered, but decided he was old enough for the truth.

“I don’t think so,” I said, “unless someone discovers a great new drug.”

He looked down and jammed his sneaker into the sidewalk. “That sucks.”

“I know hon, it does.”

At the time I was treated, there was no way to know that the doses of radiation and chemo I was given were likely more than was needed to cure my cancer. That particular protocol was used for a relatively short time before doctors discovered that they could treat Hodgkin’s Disease successfully without causing quite so much long-term damage. My future was determined by a particular moment in medical history: Had I been diagnosed a year or two earlier, the treatment wouldn’t have been available and I would likely have died a teenager; if I’d been diagnosed a few years later, I might still be running around a tennis court today.

Somewhere between those extremes, life goes on. Julia lives in New York now, and on a recent visit home, she suggests going to an Oakland A’s game. Zach (who isn’t much of a baseball fan) offers to have dinner waiting when we get home. Julia and I share a love of sports, and the game will be extra special because her beloved Yankees are in town.

Unfortunately, a heat wave arrives with the Yankees, and we get to the stadium under a blistering afternoon sun. “I’ll drop you off, Mom,” Julia says, just as I’m about to make that request. “Go through the disabled entrance,” she adds, “so you don’t have to stand outside in this heat.” It’s easily 90 degrees and I’m taking baby steps. The air feels thick and heavy. On a good day I can walk for about 30 minutes, but hills, stairs, and heat have all become powerful obstacles.

I follow Julia’s advice about the disabled entrance, something I rarely take advantage of. I can often hide my disability by avoiding situations where it might show, though that’s becoming harder to do.

Julia parks the car and catches up with me inside the stadium. I’m relieved that our seats are in the shade and require minimal stair climbing. It feels great to sit down, and Julia quickly waves at a ballpark vendor selling iced lemonade. I’m breathing easily now, sipping my drink and starting to relax and cool down. I feel a wave of happiness as I take it all in—the noisy crowd, the players jogging onto the field, the sour-sweet lemonade, my daughter beside me.