Segment II – Clowns, Boots, & Radiation: The Surreal World of College Plus Cancer

by Rachel Trachten

1. Egg Salad

After the surgery, I begin a course of outpatient chemotherapy. At 18, I’m often the oldest kid in the clinic.

There’s always plenty of waiting there, and at lunchtime staff bring a cart with sandwiches and drinks. Sometimes volunteer clowns with giant shoes and fake red noses walk through the waiting area, trying to cheer patients up with jokes and balloon animals. Some kids smile, but others are just too sick to care.

It’s early fall, and I’m waiting with my father. On this particular day, the clowns couldn’t have coaxed a smile from me. I haven’t seen Zach in weeks, and I torment myself by imagining him at Amherst being pursued by beautiful, athletic young women, all with long flowing hair. In reality, he’s been struggling to keep up in an advanced physics class while also traveling with the varsity squash team. I wait impatiently as his letters travel from the Amherst post office to my Brooklyn mailbox. Our correspondence sustains me as a I slog through more chemo, scans, and blood tests.

My dad is gloomy too. The New York Times is on strike, which is close to a catastrophe for him. He’s flipping through some other newspaper, sighing and grumbling about inferior journalism.

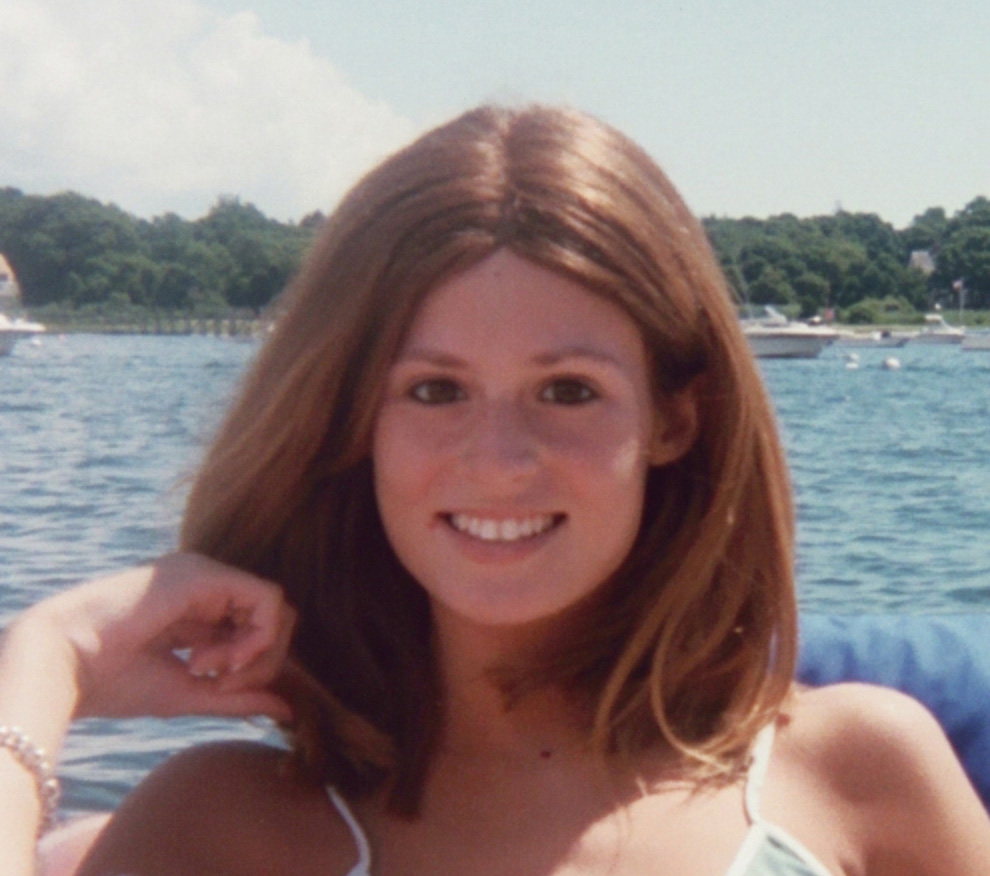

After a few months of chemo, I’m down to about 100 pounds. Most of my hair has fallen out, first in strands and then in clumps. At some point I just pull the remainder out to get it over with. George Michael comes to the rescue once again, referring me to an expert wig maker. When I look in the mirror, it’s hard to believe that I’d so recently been a normal teen, wearing my long hair in a ponytail and trying to lose five pounds so I’d look more like a dancer.

The lunch cart comes our way, and my dad folds his newspaper. “Hey, they have egg salad today!” he says, as if this is a gourmet treat. “And how about one of these milkshakes?” He means the cans of Ensure, a calorie-rich drink to help patients keep up their weight.

“I’m not hungry,” I say. When the chemo is injected into my veins, it feels ice cold and has a nasty metallic flavor. I try to disguise the taste by sucking on a handful of peppermints.

“I could go down to the deli,” my dad offers. “How about some chicken soup?”

I know he won’t quit, so I take a sandwich. It’s cut into quarters, and I stare at the four little squares laid out on a paper plate. It looks like an immense amount of food.

My dad has practically finished his sandwich when he notices me barely nibbling on mine. “You need calories,” he urges. “You could eat that little piece in just one bite.” And I could have, in a different life. But on this day I get through just an eighth of a sandwich and call it lunch.

2. Sherry & Sandy

Waiting for the hospital elevator, I might have been a visitor, decked out in my natural-hair wig and hoisting a backpack. I am in fact on my way for outpatient chemo, having come directly from a college class downtown at NYU. (I’ve enrolled there as a part-time student with assurances from Amherst that they’ll accept the course credits.) I like the fact that I don’t look like a patient—that I’ll escape that role someday and get back to being a normal college student.

Just as the elevator doors open, I see Sherry’s mom, Sandy, heading towards me. I hold the doors for her, and she smiles gratefully. “You look good, hon,” she says. “You have an appointment today?”

“Chemo,” I reply, and she nods.

My family met Sherry’s months earlier on the outpatient pediatric floor. They’d come to New York from a small town in the midwest seeking help for Sherry’s advanced bone cancer. She’s just 14.

“Sherry’s back in inpatient,” Sandy announces, as the doors close.

“Oh.” I know this is bad news. It’s just a question of how bad.

“Do you want to come and say hello?” Sandy asks. “I’m sure she’d love to see you.”

“Ok, sure,” I say, dreading the visit.

Sherry is curled up in bed clutching one of those hateful mint-green vomit basins. Tiny wisps of hair stick to her nearly bald head.

“Hey honey, Rachel came to say hello. Can you sit up?” her mom coaxes.

Sherry hardly moves, but she briefly opens her eyes and whispers, “hi.” Then she falls back to sleep.

“She can barely stay awake, poor thing,” Sandy says, pulling the blanket up around her daughter. “How’s school going for you?”

“Um, it’s going well, I’m taking modern art history and Irish fiction,” I say. As if my choice of classes mattered.

“Well, you stay in school, sweetie. That’s so important.”

“I hope Sherry will get back to school too,” I say.

“Yes, she will,” Sandy says, and I nod as if I believe her.

I try to think of another topic of conversation, but nothing seems right. “Well, I should probably get upstairs to my appointment,” I say, backing out of the room. A few weeks later I ask one of the nurses about Sherry and learn that she died a few days after my visit.

3. A Social Worker and a College Prof

My first big setback comes just a few months after starting the chemo. It’s the fall of 1978 and I’m in the student lounge at NYU. In the bathroom, I notice that my urine is an odd beige color. I know this probably means trouble.

I call Dr. Murphy from a pay phone. It’s a struggle to hear her over the chatter of students hanging out and drinking coffee between classes. But I’m pretty sure she’s telling me to come right to the hospital. She suspects that I have hepatitis and, as usual, she’s right; I’m soon an inpatient again.

The days pass in a blur. Sleep, blood tests, nurses coming and going.

One day a woman comes into my room and introduces herself as Lynn, a hospital social worker. Fine with me, no needles involved. After going through the basics, I find myself pouring my heart out, telling Lynn all about Zach and his recent letter saying that he loves me.

Zach and I have been keeping up a steady stream of cards and letters. I send news of blood and platelet counts along with worries over exams, complaints about the subways, and descriptions of foods I’m eating to keep my weight up. In one letter, I tell him that I’d discovered a new node in my neck and felt paralyzed with panic, assuming it meant the Hodgkin’s was getting worse. I’d gone right to the hospital, where Dr. Murphy assured me the node was harmless. Zach sends newsy notes about life at Amherst, describing his struggles with physics problem sets, his wins and losses on the squash court, and a budding romance between two of our friends.

What I’m not aware of at the time is how much Zach is suffering. His letters are mostly upbeat, but years later he tells me that he was constantly worried about my health. He describes going to frat parties almost every night, trying to numb himself by drinking beer, and dancing until he’s exhausted enough to sleep.

He’s also falling behind in his course work and asks his Russian literature professor for an extension on a paper. Stanley Rabinowitz is a renowned scholar whose lectures are enormously popular with students. He takes the time to ask Zach about his life, and Zach tells him about my illness. The professor gives Zach some advice that sounds obvious but has a profound effect. “Try not to worry about things before they happen” is the essence of his wisdom, and Zach takes it to heart and finds healthier ways to cope.

After a few weeks, I recover and leave the hospital, glad to have met Lynn. As an outpatient again, I pop into her office for a long talk or a quick catch-up every chance I get.

4. Stick It!

I barely say a word as the curly-haired nurse sticks her needles into my tiny veins over and over, trying to get the required tubes of blood.

I always try to be friendly to the nurses, and most of them are friendly right back. Pediatric nurses are accustomed to screaming babies and thrashing toddlers, but I’m someone who can be reasoned with, even talked to as a peer of sorts.

The curly-haired nurse barely acknowledges me. She offers no sympathetic smile, just gets right down to business with her rubber gloves and syringe. She doesn’t even suggest warming my arm up to make the veins bigger. Then, she becomes increasingly annoyed as my delicate veins roll away from her probing needles. Black-and-blue marks pop up wherever those needles pierce my skin.

My response is to burst into tears as soon as she leaves the room.

“Where’s your fight?” I want to ask my teenage self. “Don’t you hate her?”

What if I’d pulled my arm away and simply refused? What if I’d marched out of that hospital for good?

5. New Boots

Dr. Murphy is petite and gray-haired, looking more like a midwestern grandma than one of the country’s leading pediatric oncologists. I eventually learn that she was one of only two women in her med school class back in 1944. At Sloan Kettering she collaborates with another female oncologist, Dr. Charlotte Tan, who looks to me like a Chinese grandma. I’m fascinated by the way Dr. Murphy refers to her colleague simply as “Tan,” as in, “I’ll speak to Tan about that.”

When I become Dr. Murphy’s patient, I’m 18 and she’s about 60. Just as I’m starting treatment, I’m having terrible insomnia. Won’t she please, please give me some sleeping pills? She listens carefully but won’t do it. “If you can’t sleep, just rest,” she tells me. I protest, but she won’t budge.

As the months pass, we get to know one another. I come to every appointment with a written list of questions, and she always tries to answer each one. She’s a pediatrician but treats me like an adult.

One day in clinic I show her an itchy rash on both of my legs, from my ankles up to my knees.

The rash is getting worse every day, and I’m starting to panic. She studies my legs, and I ask if I should see a dermatologist.

“How long have you had this?” she asks.

“Just a few days, but it’s getting worse.”

She looks over at the leather boots I’ve left in the corner of the room. Stylish brown boots, very chic.

“Did you just buy these?” she asks. She picks one up, touches the stiff leather.

“Yes,” I say, surprised at her interest in my footwear.

“They must be awfully tight around your legs,” she says, and then I get it.

She picks up her prescription pad, scrawls a few words and hands it to me. “Rx,” it says. “New boots!”

6. Zapped

As I’m going through it, the radiation doesn’t seem like a big deal. It happens at the halfway mark of the treatment, with three cycles of chemo behind me and three to go. I show up at the hospital Monday through Friday for three weeks running. The visits are quick: I lie on a table under a futuristic-looking machine and the radiation is beamed through me. My chest and back have been permanently tattooed with tiny blue-grey dots to guide the beam.

Some patients might have questioned the long-term safety of radiation treatment, but I accept it as something I need in order to get well. I’m relieved to find that it’s quick and painless, practically a vacation compared to the nausea and needles that come with chemo. Sometimes I even go out for lunch or to the movies afterwards.

Little did I know that what felt like a respite at the time would have such a powerful effect on my future health. Many years later, a renowned cardiologist at Stanford will tell me, “You got zapped.”

7. How’s it Going?

Happy day! Now that I’m halfway through the chemo, Dr. Murphy has given me the okay to return to Amherst. I’ve spent months lobbying for this, reassuring her that I’ll really, truly take good care of myself.

“You college kids never know when you’re tired,” she tells me. But my blood counts improve and she works out the medical logistics with a cancer specialist near Amherst. I’m all set to get back to college life. I’ll take a half-load of classes, live on campus, and continue chemo treatments nearby.

But once I arrive, I feel completely out of place. I’m surrounded by healthy young adults, the sort who wake up early to jog or swim laps before breakfast. It’s February, and most students wear nothing warmer than a down vest, while I’m bundled into sweaters and a bulky jacket. At night I’m exhausted but too anxious to sleep. Zach tries his best to help, but between science labs and travel to squash tournaments, his schedule is packed. Afraid to burden him, I conceal how stressed and alienated I feel.

A few close friends know what I’m going through, but what should I reveal to casual acquaintances? When I opt for the truth, some people are effusively sympathetic and tell me I’m “so brave” or look at me with pity. Others just change the topic. I hate all of these responses and decide to say less. Whenever someone asks, “How’s it going?” (a common refrain on campus), I smile and say, “Good!” (the expected response).

Then, the wig. To take a shower, most students simply walk to the dorm bathroom wearing a robe. I can manage this, but what about the wig? Should I walk down the hall wig-less with a towel around my head? Or should I wear the wig, then hang it on a towel hook? What if someone sees it hanging there? I finally decide to leave the wig in my room. Hoping I won’t run into anyone on the way, I scurry to the bathroom clutching a towel around my bald head. I feel nothing like a normal college student.

8. Sisterhood

Women take over the men’s bathroom at the Holly Near concert that February night. It’s 1979, and I’m with Amy, my best friend at Amherst. She and I had hit it off as soon as we’d met, and I love her toughness and honesty. Naturally, Amy joins right in when the women waiting in line decide that the men’s room is up for grabs too.

Amy and I are enthralled by the music and the proximity to so many like-minded women. We both identify as feminists at a college that has only recently gone co-ed. After visiting the Women’s Center during one of my first days at school, I’m surprised by the reactions I get from other female students: “Why would you go there?” and “Don’t you know they’re all man-hating lesbians?”

That night Holly Near and Meg Christian sing about sisterhood and love and political power. I’m eager to escape into the music and forget that I have cancer.

Amy and I can usually talk about anything, but she consistently avoids the topic of my illness. Leaving the concert, she says, “Let’s do a radio show about women’s music.”

A friend at the college radio station can help with the technical side. All we have to do, Amy says, is write a script, choose the music, and tape the show. I have no idea how we’ll manage this, but Amy is confident.

Two weeks later, we’re ready to record. It’s evening, and snow falls steadily as we enter the studio. I do my best to stay alert, but I’m exhausted from the chemo. Amy is focused on the radio show, and I feel hurt and abandoned as she acts like I’m just fine. Months later, she confides, “I felt so close to you that I couldn’t accept how sick you really were.”

9. A Small Rash

About two months into the semester, I develop a small rash on my left side. It doesn’t look like much at first, but it persists, reddens, forms small crusts. I show it to my local oncologist, who sighs and says I have shingles, a nerve inflammation that’s common when your immune system is weakened by chemo. He prescribes codeine in case the rash becomes painful.

I fill the prescription but assume I won’t need anything more than Tylenol.

Dr. Murphy suggests I return to New York, but I resist. She reluctantly agrees to let me track how quickly the rash is spreading. Luckily, Zach is not at all squeamish. In fact, the experience of my illness has convinced him to go pre-med, a decision that makes perfect sense given his interest in both science and the humanities. With help from another pre-med friend, he outlines the contours of the rash with a marker to track its progression.

By the next day, I’m popping codeine every four hours. And a day after that, the red spots swell and spread into ugly blisters. The rash has more than doubled in size, and codeine isn’t enough to ease the pain. My mid-section looks like some kind of ghoulish topographical map.

Zach calls Dr. Murphy and describes the blisters and my pain level. “Put her on a plane today,” she says, and my semester is over. I fly back to New York dazed and sleepy from painkillers; my parents practically carry me off the plane. We go directly to the hospital, where I’m quickly admitted. Years later, my mother tells me she nearly blacked out when she saw those blisters.

10. Girlfriends

I’m finally well enough to leave the hospital. I’ve been an inpatient for nearly two months, battling shingles, meningitis, and other complications from the chemo. I later learn that my survival was uncertain, but at the time I’m too sick to even wonder about it.

During these months, my contact with the outside world is limited to staff and visitors. Once I start feeling better, I take slow walks round and round the nurse’s station. Two close friends, Allison and Lisa, are on spring break from college and come to see me. If they’re shocked by how frail and bald I am, they never let on. They bring Italian bakery cookies and gently rub my fuzzy head. Many years later, Allison tells me that when she first learned about my diagnosis, her mother told her not to look it up in the encyclopedia, but she did anyway.

Allison and I became nearly inseparable starting in sixth grade, and Lisa made it a threesome when we got to junior high. With so much shared history, the three of us can relax and giggle even in a cancer hospital. When the nurses let them bring me out to the deck in a wheelchair, I can almost convince myself we’re just out on the town.

The day I’m discharged from the hospital, I walk along the Manhattan sidewalk like a country bumpkin gaping at big city life. My dad drives to Brooklyn and stops at a local market, but I stay in the car, watching the scene around me as if it’s a movie. People come and go with bags of groceries, small children in tow. I’m feeling sleepy and almost drift off for a nap, but the world pulls at me. I find myself thinking about Lisa and Allison and wondering when they’ll come home for the summer. I imagine going out to Sunday brunch and catching up on their lives and dating adventures. Months later, Zach and I rent a basement apartment in Greenwich Village. Before we move in, Lisa and Allison show up with buckets and cleaning supplies and help us scrub every inch of that apartment.